A History of Penguin Books and the Mass Market Paperback

In the early twentieth century, mass market reading materials were of notoriously low quality. Riding the coattails of the penny dreadfuls of the late nineteenth century, inexpensive newspapers or short leaflets with serialised stories were all the rage for the lower classes, who often could not afford full-length books, but loved to read as a leisure activity.

In 1934, Sir Allen Lane, a young publisher, stopped at the station book stall at Exeter St Davids on his way to London after visiting his friend Agatha Christie. He found that all the available books were low quality and overpriced.

He decided there needed to be a line of high quality paperback books offered at an affordable price. And thus, the Penguin imprint was imagined.

Democratising reading with mass-market paperbacks

Lane and his two brothers formed the Penguin imprint, originally under another publisher, but quickly went out on their own. The publishing industry didn’t believe that making quality books at such a low price — sixpence at the time — could possibly turn a profit. Lane was able to negotiate the rights to print some books at a much lower rate than he might otherwise because the publishers didn’t believe the venture would last very long.

But Woolworths saw the value in what Lane was trying to do and placed an initial order for 63,000 books. That single order paid for the project outright and within just two years of its inception, Penguin had sold over a million books.

Other high street stores followed Woolworths’ example and helped Penguin essentially democratise quality literature so that it was available to the masses — and change publishing forever. Other publishers in the UK, the United States, and elsewhere, quickly recognised the success of Lane’s strategy and started making literature of all kinds available at more affordable prices.

Our 2022 winter window display, featuring Popular Penguins and a few stuffed penguins!

Part of the war effort: books for the troops

During the Second World War, the demand for books was high, but the supplies to print them were very hard to come by.

But Lane proved extremely good at striking deals that would keep his presses running. When rationing began in 1940, the Ministry of Supply issued paper based on how much the company had printed in the previous years; because Penguin were producing mass quantities of paperbacks, they got a greater allotment than other publishers. Lane struck up a deal with the Canadian Armed Forces to provide books for their troops, and was paid in tons of paper, and in 1941 he struck a similar deal with the War Office.

Penguin essentially had a monopoly on books made specifically for overseas distribution to the troops, and by the time the war ended, their established paper supplies left them in a better position than other companies as rationing continued.

Challenging the status quo

In 1960, Lane decided to publish Lady Chatterley's Lover by D. H. Lawrence in the United Kingdom. His decision resulted in a public obscenity trial, R v Penguin Books Ltd. It was a gamble, but just as he’d correctly judged the public’s appetite for better literature in the 30s, Lane also correctly judged their appetite for Lady Chatterly’s Lover. The trial helped drive the sale of at least 3.5 million copies of the book, and Penguin's victory in the case marked them as a bold, fearless publisher and heralded the end to the censorship of books in the UK.

And that wasn’t the last time Penguin would challenge the status quo in publishing. Notably, they published The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie in 1988, which resulted in his having to go into hiding for some years after the Ayatollah of Iran issued a Fatwa against him for it.

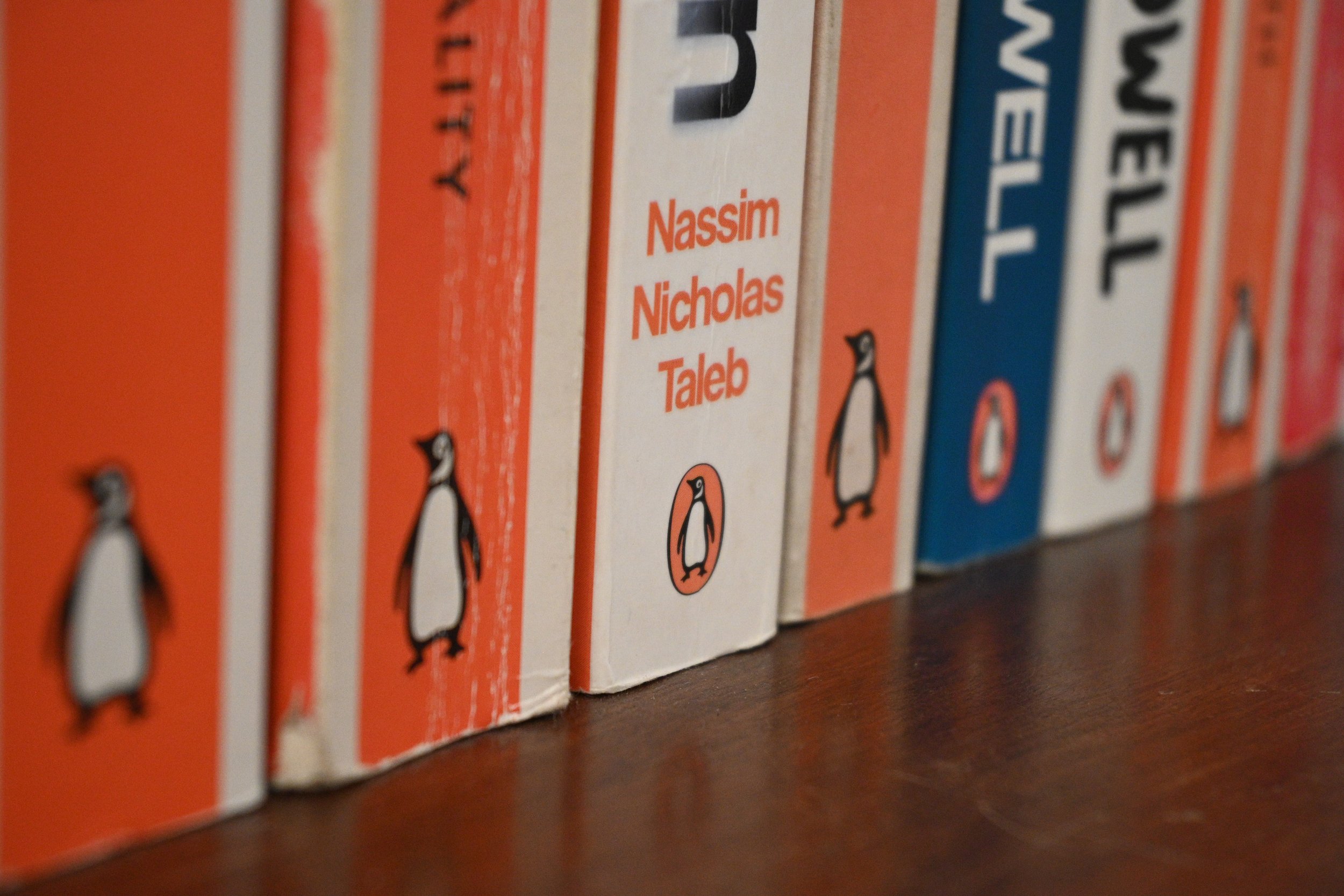

Those iconic covers…

Good design was important to Penguin from the beginning. Lane wanted to differentiate Penguin books from the cheap, low quality stories otherwise available, most of which had lurid covers to tempt readers.

Penguin books followed a simple design of three bands, the top and bottom colours corresponding to the genre to which the book belonged, and the middle white band containing simply the title and author of the book. Lane resist any cover illustrations at all, but some simple line drawings were added over the years.

Orange indicated general fiction, green for crime fiction, cerise for travel and adventure, dark blue for biographies, yellow for miscellaneous, and red for drama.

The Popular Penguins series we know - here in New Zealand - are all in orange, and not colour-coded in the manner of the original designs. This orange collection is exclusive to the New Zealand and Australian markets too, so your friends visiting from overseas might be quite surprised - and delighted - to stumble upon them.

Between 1947 and 1949, Jan Tschichold, a German typographer, created a set of influential rules of design principles for the company, known as the Penguin Composition Rules, a four-page booklet of typographic instructions for editors and compositors.

In the 1960s, new printing techniques made it possible to reproduce art and photography cheaply, paving the way for new, graphically designed covers. This dramatically altered the look of the famous Penguin brand, though it retained the classic colour coding.

A close-up of our 2022 winter window display.

Penguin Random House today

In 2013, Penguin and Random House combined to create a global publishing house. The company re-released a Penguin Classics series in 2015 to celebrate the company’s 80th birthday, offering paperback classics with a classic cover design for just 80p. The promotion sold 70,000 copies in its first week.

Today, the company is distinguishing itself with a campaign for inclusion. It was the first publishing company not to require a University degree for all its jobs. They launched a Creative Responsibility manifesto, outlining their commitments to inclusion and sustainability. And they created a campaign to seek out and publish new and under-represented voices in the UK market.

And in 2017, an orange memorial plaque was installed at Exeter St David’s railway station to honour Sir Allen Lane and the incredible legacy he created with Penguin books.