The History of Jigsaw Puzzles

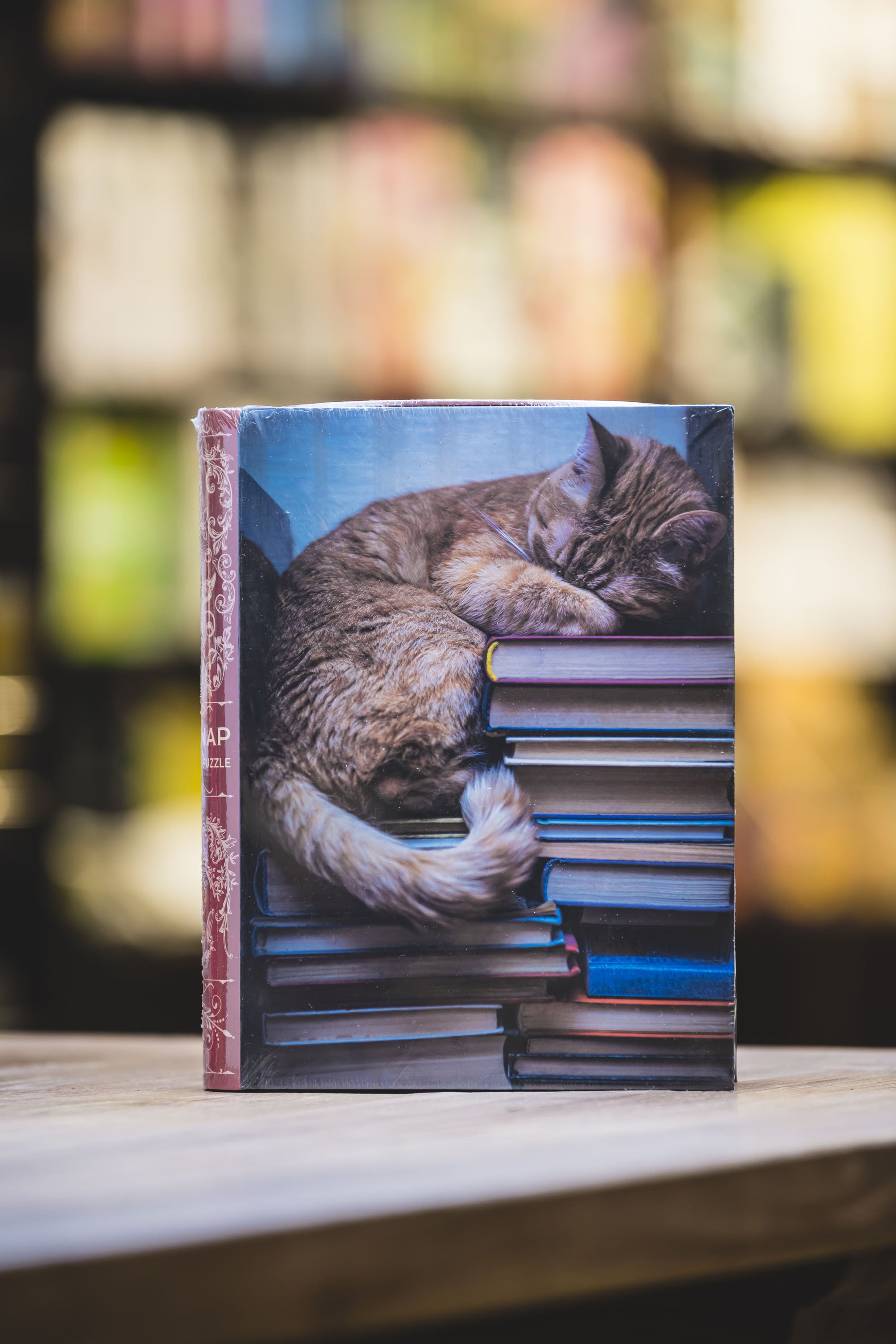

Perhaps because we opened during the pandemic, when puzzles were seeing a resurgence in popularity, jigsaw puzzles have consistently been some of our bestsellers since Mrs Blackwells began.

Some historians say we are in the third historic “puzzle craze,” but where did it all begin?

Let’s start off with some terminology (useful for crossword puzzles and impressing local dignitaries at cocktail parties):

The term “jigsaw” puzzle entered use around the 1880s, when the treadle jigsaw was invented. It was operated with a treadle — think of the pedal on antique sewing machines — and allowed designers to produce more intricate puzzles more quickly.

The round tabs that stick out from a standard puzzle piece shape are called interjambs. The hollows into which the tabs fit are called blanks.

Whimsy pieces are puzzle pieces cut into the shapes of objects, usually of a theme with the image on the puzzle. (Like a piece shaped like an elephant in a puzzle with a scene of an African safari.)

The first jigsaw puzzles weren’t made on jigsaws

A cartographer and engraver named John Spilsbury is credited with creating the first jigsaw puzzle, then called a dissection. He took one of his maps, glued it to a piece of hardwood, and then cut along the boundaries of the countries to produce a puzzle that could be used in schools to help teach geography.

The puzzles were a hit, and the concept was soon copied by others and expanded to include religious and pastoral scenes, still mainly for teaching purposes. Around the mid 1800s, puzzles became popular with adults as well as children. Gift giving, especially for Christmas, was also becoming more popular, and educational games like puzzles were favourite gifts.

Modern advances in jigsaw puzzles

Around 1880, the treadle jigsaw was invented, which made the intricate cuts necessary to create the puzzles easier to produce. Printing techniques also became more sophisticated, which led to better, more colourful images for puzzles. And plywood was also invented, creating a more affordable alternative to the hardwoods that had been used up to that point.

All of these advances led to a dramatic rise in popularity for puzzles toward the end of the 19th century and into the 20th. A May, 1908 New York Times headline proclaimed:

New Puzzle Menaces the City’s Sanity.

Young and old, rich and poor, all hard at work fitting cut-up pictures together. Solitaire is forgotten. Two clergymen, a supreme court justice, and a noted financier among the latest converts to the craze.

Despite the sensational headline, puzzles were still mainly for the wealthy at this time, although puzzle clubs and rental libraries tried to offer the games more equitably. Puzzles cost around $4 each at this time in the U.S., and the average worker earned only $12 per week.

Parker Brothers employed mostly women to produce their puzzles. The women were paid by the piece, and expected to produce a minimum of 1,400 pieces per day.

In the 1920s, companies, especially travel companies, started producing puzzles as marketing materials. Cruise liner Cunard produced postcard-sized puzzles that they sold as souvenirs onboard their cruise ships, including one of the Queen Mary before she ever sailed.

By the 1930s and the Great Depression, puzzles enjoyed a great deal of popularity. They were an inexpensive way to be creative and pass the time. In 1933, games manufacturers were producing 10 million puzzles per week. Victory Puzzles was the first to put the finished picture of the puzzle on their boxes around this time — before that, having the image for reference would have been considered cheating.

Until war broke out, puzzles were still largely made of wood, but when plywood became in short supply, puzzle companies started using cardboard. Initially the cardboard was of very poor quality, but it did make the puzzles cheaper. The price of a 300-piece puzzle dropped to about 25 cents. Manufacturers introduced weekly jigsaw puzzles, available at newsstands, that were wildly popular. Puzzle contests with monetary prizes also became popular during the Depression.

Puzzles today

Today, the majority of puzzles are made from quality paperboard and cut with a large press and a custom blade called a puzzle die. Think of a huge cookie cutter with the shape of all the puzzle pieces.

New technology also allows for laser cutting which can produce more intricate shapes for pieces and use materials like acrylic and hardwood. There are even 3D puzzles made of styrofoam, acrylic, or wood. Digital puzzle games and apps are also popular for the challenge of solving jigsaw puzzles that can be taken anywhere.

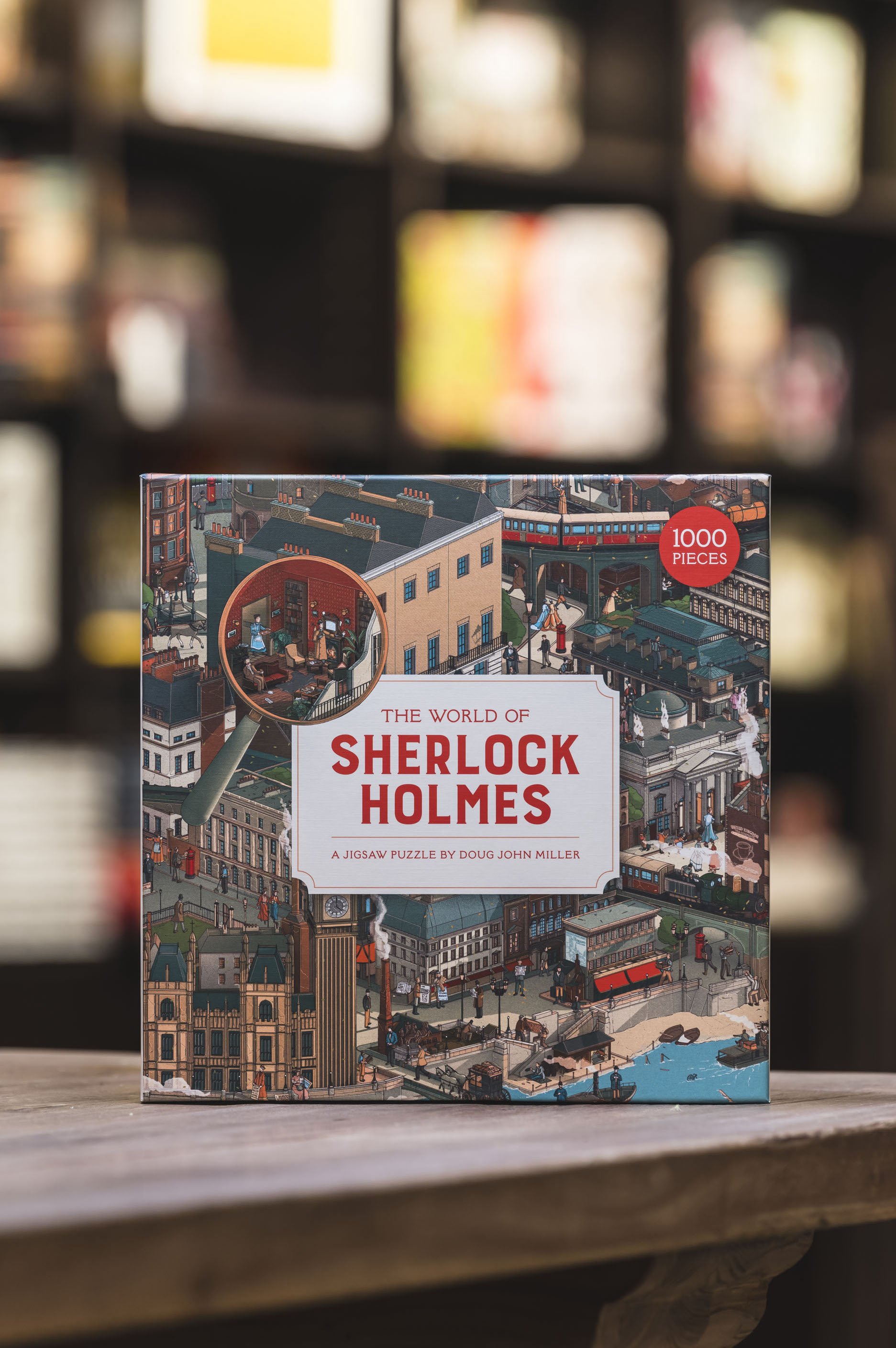

Puzzles come in all shapes and sizes, with as few as 4-9 pieces for very young children, and up to hundreds and thousands for puzzles geared towards older children and adults. The most common layout for a thousand-piece puzzle has edge pieces numbering 38 by 27 — which means there are actually 1,026 pieces to the puzzle in total. The largest commercially available jigsaw puzzles have more than 50,000 pieces!

In the autumn of 2020, as the first lockdowns began for the Coronavirus pandemic, there was a surge in demand for puzzles. Puzzlemakers saw demand increase by as much as 300-400%. And with pauses in production, game companies and retailers quickly sold out.

Why such a demand for puzzles? Well, it seems a natural sort of activity when one is stuck at home, trying to avoid doom scrolling. Plus, a 2018 poll found that 59% of people polled found doing puzzles relaxing, and 47% felt the activity relieves stress.

And puzzling may be good for you as well: The Alzheimer Society of Canada suggests that doing jigsaw puzzles can help keep the brain active and may reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease.

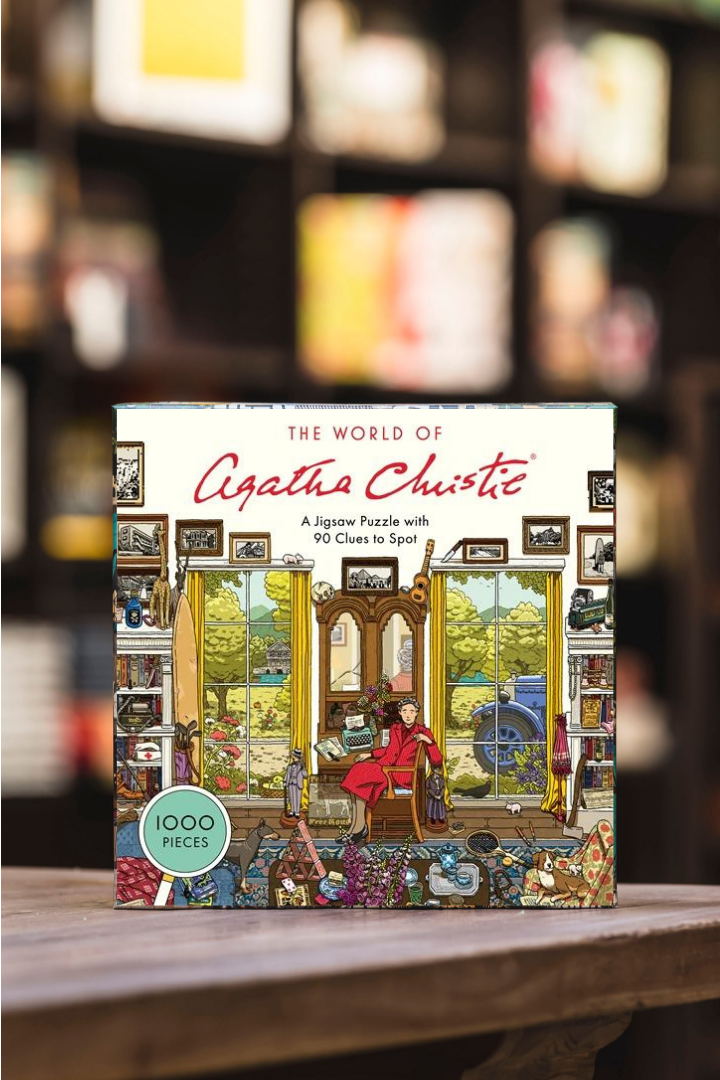

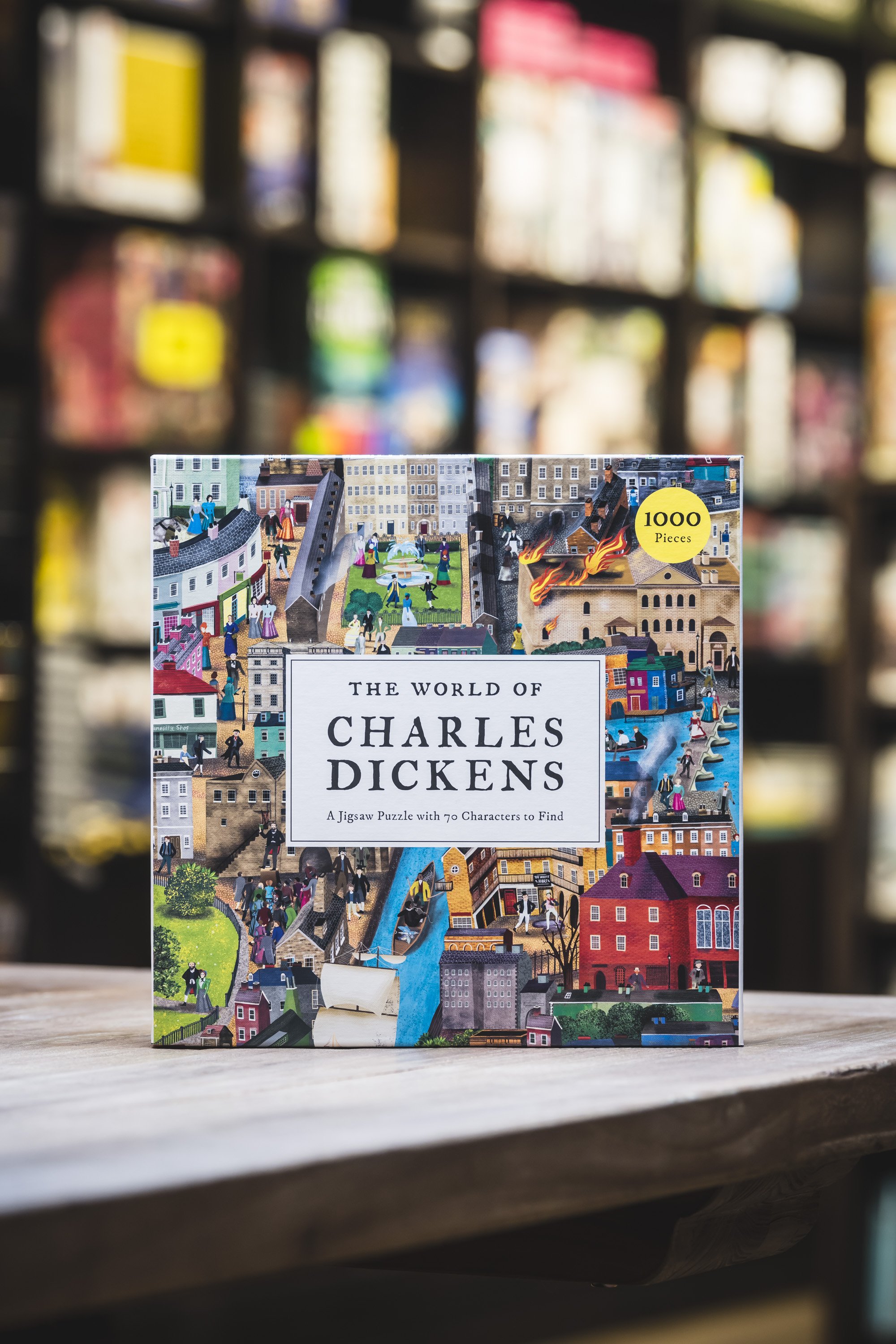

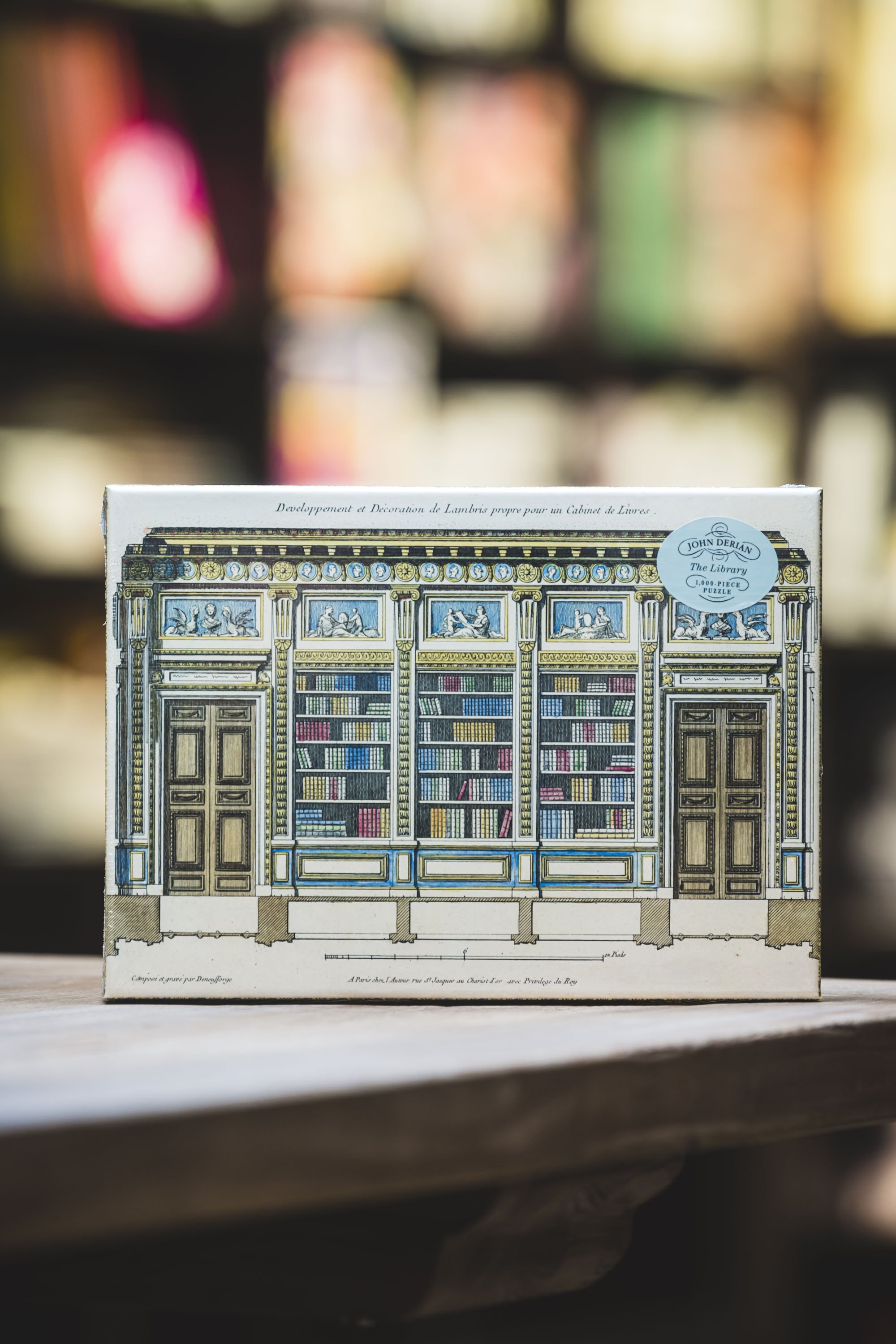

Looking for your next puzzling challenge? Drop into our shop or visit us online for our full selection of jigsaw puzzles.