Poetry 101: A Beginner’s Guide to Reading (and Enjoying) Poetry

If your only exposure to poetry was required reading in school or nursery rhymes you read as a child (or to your own children), you might be hesitant to add poetry to your reading list. But there’s a world of poets and poetry beyond what you might have been assigned to study, and if you have even a passing curiosity, that world is worth exploring.

There’s as much variation in poetry as there is in any art form — from sweeping classical epics to the deep simplicity of haiku, and from the lyrics of contemporary hip hop to the sonnets of Shakespeare.

As a poetry beginner myself, I know it can be intimidating. Where do you start? Should you read lots of poems at one sitting or read one many times over? Do you have to understand terms like “scansion” and “meter” to really get what the poet was trying to achieve?

How to choose what poetry to read

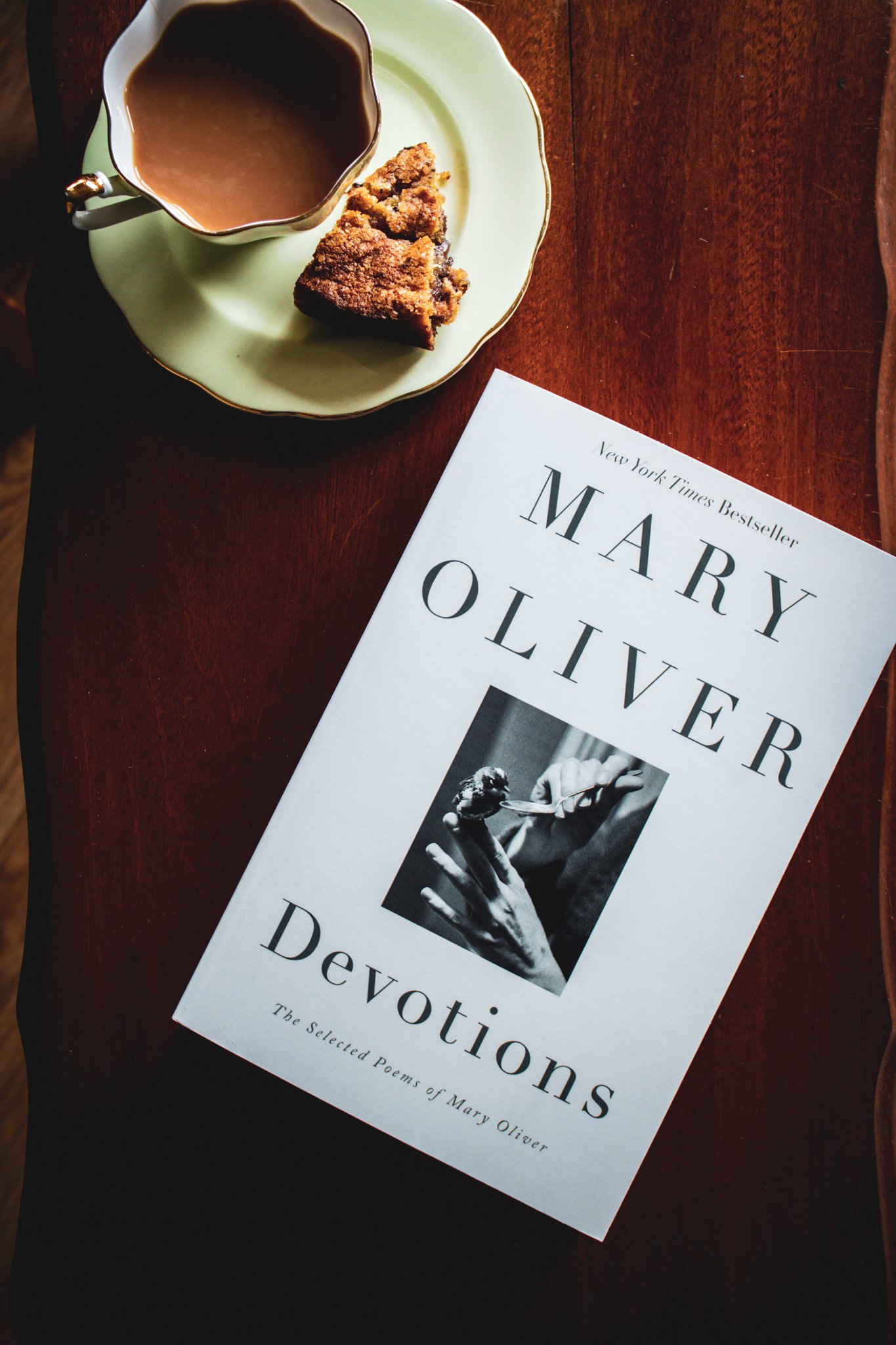

The best advice I’ve been given is to start with what you like. If you have a poet you already admire, or even a single poem, start there with more of that poet’s works. Then you might follow the breadcrumbs and trace back some of their influences: who do they admire and credit with influencing their work?

If you don’t have a particular poem or poet as a starting point, starting with a broad sampling could be a good way to begin. Poetry anthologies are an excellent place to start, as they’ve been curated for you and often come with some context or analysis.

The Fire of Joy is one such anthology, collected by Clive James, and offered with a personal reflection or commentary on each.

Literary magazines and Poetry Magazine can offer another sampling of contemporary poems and poets that might spark your interest. There are daily poetry emails you can sign up for from Poets.org and the Poetry Foundation. And there are even poetry podcasts, like Poetry Unbound that might whet your appetite.

Explore until you find something that piques your interest and provides you with a particular avenue to direct your explorations. Don’t worry about trying to read the classics or the masters — unless that is what interests you.

How to think about poetry

I think my favourite piece of advice about how to enjoy poetry comes from an NPR piece, which says, “Don’t worry about ‘getting it.’”

In school, you were probably asked to analyse poems and write essays about them — and it may have felt (or actually been true) that there was a right and a wrong answer.

In truth, there’s no more a right answer to what a poem means than there is a right way to get started reading poetry. A poem might mean different things to different people; it might even mean different things to you reading it at different times of your life.

Thankfully, no one is going to ask you to write an essay about that poem you just read or defend your opinions of it. You’re allowed to feel whatever you feel when you read it, and interpret it in a way that makes sense to you at the time.

There’s no quiz at the end!

That said, if you find yourself curious about the choices poets make — why this poet chose a strict rhythm and rhyme scheme and that one chose free verse, why the poem is in a particular shape, why they break the lines where they do — you might decide to learn a bit more about the tool in a poet’s toolbox.

Actions & Travels is a wonderful exploration of how poetry works through a collection of 100 poems. It’s broken into chapters that explore things like imagery and form, simplicity and resonance, and much more.

Start by just reading the poem as you’d normally read anything. As you go, take note of where in the poem you react — a particular phrase that makes you pause, a line that makes your stomach churn, a stanza that makes you do a double take and read again.

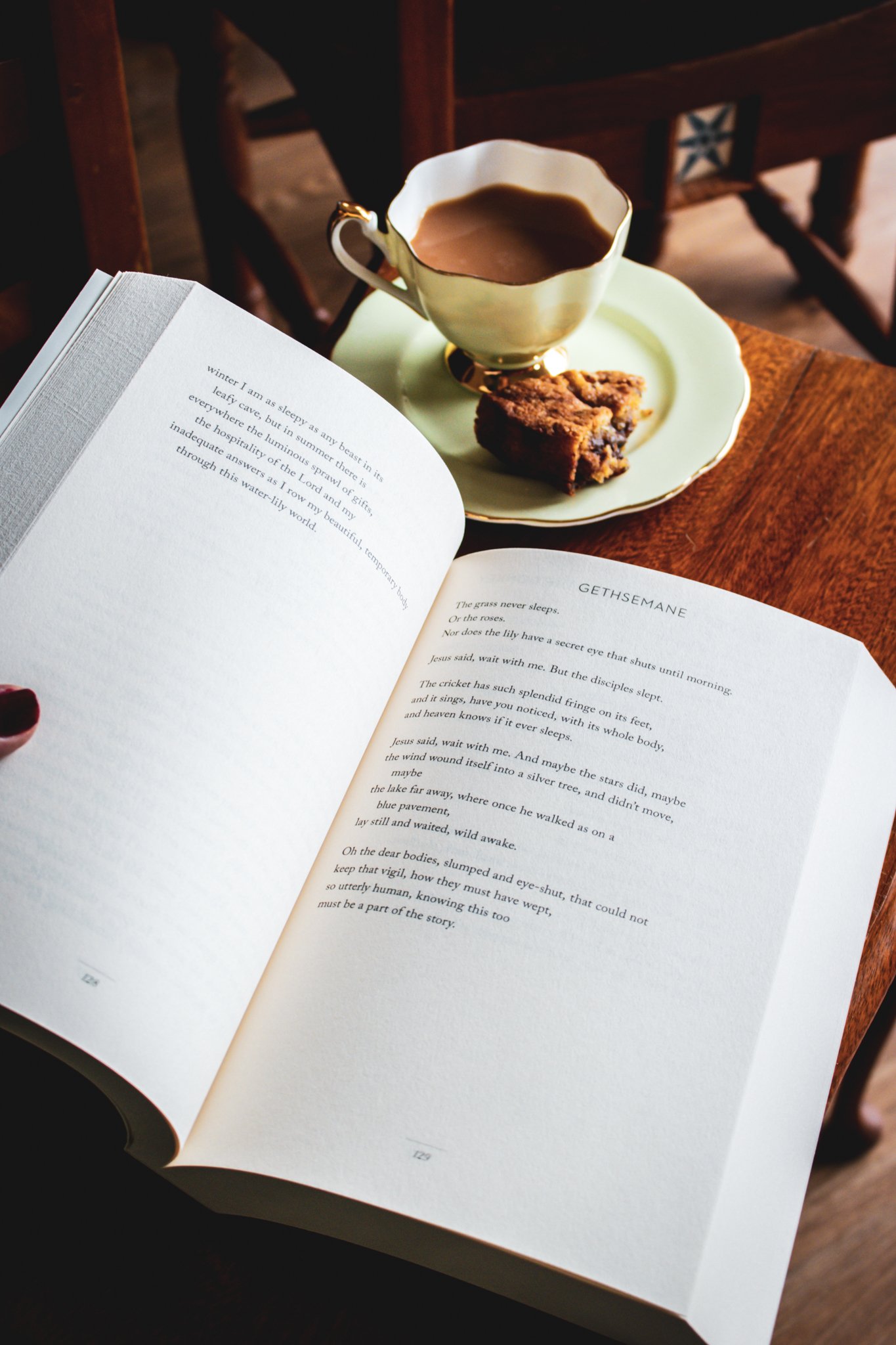

When you’re struck by a particular poem, you might want to go a bit deeper. Re-read it again and pay a bit more attention to how each line is formed, how the words are strung together or deliberately broken apart.

Generally, when thinking about a poem, start by thinking of the images it presents. Poetry can be a very visual medium, and those images frequently give insight into the poet’s meaning or intentions.

Consider word choice. A poet never includes a word at random; each one is chosen with intent. Think about particular juxtapositions of words, images, or themes.

Look for repetition and patterns of sounds, words, phrases, or ideas that might be used to amplify, emphasise, or change the speed or rhythm of a poem.

And think about the form.

There’s a huge difference between a free verse poem and a poem that follows a very specific pattern like a sonnet, a villanelle or even a haiku.

Ask yourself why the poet might have chosen that particular form for that particular poem.

If you don’t know much about the different forms, a quick Google search can help you identify if a poem is written in a particular form, and some of the history and meaning of the form.

Finally, you might want to learn more about the personal history of a poet you admire. Learning about their background, even where they were or what was happening in the world when they wrote a particular piece can frequently provide even deeper insights.

Read — or listen — out loud

Finally, remember that poetry was first an oral art form and most, if not all poetry is meant to be spoken and heard aloud.

When you find yourself taken with a particular poem, try reading it out loud and notice if it makes you feel any differently about it.

Better still, attend a poetry reading and listen to a performer or the author deliver a poem. You may find it’s a very different experience of the work to reading it silently to yourself.